Article from The Sun-Herald's Explore magazine.

By Rod Smith

LIKE a signpost, the sun-bleached King Billy pine stump marked the top of Barron Pass and the end of our struggle up the steep, rainforested slopes.

For the past two hours life had been reduced to a slow trudge up to the mountain pass which marks the psychological, if not lineal, half-way point of the 50km return trip to Frenchmans Cap in South-West Tasmania.

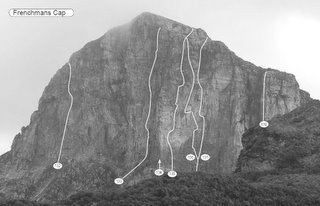

With the end of the climb up to the pass and our weighty packs off our backs, our surroundings came into sharp focus on this hot, Tasmanian summer day. Out of a near cloudless western sky loomed our goal, the massive quartzite half-dome of Frenchmans Cap.

Like a single tooth biting the blue sky, the 1446m peak’s sudden re-emergence – after a short, tantalising glimpse at the start of the walk the previous day – stripped away our fatigue. It was a view that held us for a good 40 minutes at Barron Pass, much longer than we had so far lingered anywhere else on the walk in.

It was a view that also meant just two hours more walking to our second night’s accommodation, the sturdy little 16-berth hut beside Lake Tahune. From Tahune Hut we planned to make our bid for the summit of the Cap and enjoy the expansive views into the surrounding World Heritage wilderness, weather willing.

Our trip had begun at 10am the previous day when our six-man party had travelled for four hours from Launceston in a hired 12-seater bus.

The Frenchmans Cap National Park trackhead begins on the Lyell Highway, about 55km from the West Coast mining hub of Queenstown. On the way there we passed through Derwent Bridge and the terminus of the renowned Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park Overland track. But where the Overland Track is so popular that a one-way walking rule and limits on walker numbers have been introduced to regulate the booted hordes, Frenchmans Cap National Park remains comparatively low-key.

But as the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service warns in its literature Frenchmans “is considerably more arduous than many other Tasmanian walks, including the Overland Track”.

The Frenchmans Cap walk traditionally begins, as did ours, with a group photograph beneath the Frenchmans Cap sign. After registering our walk details in the track logbook we made the pleasant 10-minute walk to the banks of the Franklin River.

It’s the same Franklin that in 1983 international outcry and a High Court ruling saved from becoming part of a new hydro-electricity impoundment.

Two years after that victory, in 1985, a teenager and his mates hauled themselves and their packs across the Franklin in a flying fox as they embarked on their first ever Frenchmans Cap walk. Twenty-one years later and I’m no longer a teenager, I’m back with a different set of mates but disappointingly there’s no flying fox. Nowadays a springy one-at-a-time suspension bridge gets you across the river in seconds.

After crossing the river our party sorted itself into two groups: father and son Simon and Peter Kearney would travel at their own pace, probably camping at one of the tent sites. My group of four was determined to reach the spacious 20-berth hut at Lake Vera, 16km away.

The decision to break our group into two parties was both expedient and safe: Each group carried tents and an EPIRB (or Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon) as well a pair of UHF walkie-talkies tuned to the same channel. In the event of injury or sudden and severe weather we could make camp, communicate with one another or, as a last resort, set off an EPIRB and wait for the rescue helicopter to come.

For Simon the trip was something of a personal odyssey: his maternal great-grandfather was none other than J. E. Philp the hardy bushman who, with two companions, was contracted to cut the original Frenchmans Cap track in 1910 as a prospector’s track. Philp’s exploratory efforts are remembered in landmarks like Philps Peak, Philps Lead and Philps Creek. Lake Vera is named after Philp’s wife, Simon’s great-grandmother.

The Parks and Wildlife Service warn prospective Frenchmans Cap walkers that the track in general has a surface that “may be rough and muddy over extended sections, especially across the Loddon Plains”. This is an understatement. The Loddon Plains are always rough and muddy, hence their nickname the Sodden Loddons.

For Frenchmans Cap walkers this seemingly endless buttongrass bog is the first day’s major obstacle. Admittedly the first hour away from the river is a long uphill drag around Mount Mullens, but it is not as mentally demanding or physically taxing as the Sodding Loddons.

Unlike many popular Tasmanian walking tracks, only a tiny part of the Loddons has been boarded. This has resulted in an ever-spreading network of unofficial tracks as successive walkers attempt to avoid the worst of the mud.

Make no mistake, whatever strategy you use you’re going to get very muddy. After carefully and cleanly negotiating the early sections you’ll invariably step onto a solid-looking piece of track and suddenly it will swallow you up to your knees. After spells of wet weather that could mean sinking up to your waist.

It took our four-man party three hours to cross the plains using a combination of hopping from tussock to tussock, edging carefully around the bogs and charging through and hoping the mud wasn’t as deep as it looked. We baked beneath a sun that on that first day reached 31 degrees C in Queenstown. We drank litres of water from the many small streams that flow along the way, even in the height of summer. Then suddenly the track veered west and began climbing a gentle hill. We had cleared the Loddons.

Encased in an armour of mud up to our knees, we took a short break and snacked on that most ubiquitous of bushwalker delicacies the dried fruit and nuts mix called scroggin. Keeping up energy stores by staying well fed and thus fuelled is as important as being well hydrated.

As we sat dozens of voracious march flies descended upon us. Slow, dopey and resembling a blowfly, march flies are perhaps the least enjoyable aspect of summer walking in Tasmania. They disappear when you’re move but attack relentlessly when you are stopped. The only bonus is that they’re quite easy to swat and so provided us with ongoing opportunities for vengeance, when we could be bothered.

Aside from the flies, the thought of clean clothes and the night’s hot food brought us to our feet and we pushed on towards Lake Vera Hut. With the Loddons behind us we reasoned that the day’s obstacles had disappeared. Not so. As would happen a number of times on this challenging walk, one obstacle was replaced by another.

The steep drag up through the temperate rainforest of Philps Lead sapped our final reserves of strength. Conversation ceased and all of us could feel the twitch of muscles starting to cramp, no doubt due to the salt loss from our voluminous sweating. Even as we began the descent into Lake Vera there was little to be said.

After almost eight hours of walking we just wanted to get there.

It’s amazing what a cup of pea and ham soup, a wash down in a mountain stream, dry clothes and the prospect of a soft, inflatable Thermarest mattress will do for the psyche of the exhausted bushwalker. Within two hours of taking up residence in the bright and cheery circa 1979 Lake Vera Hut our enthusiasm had returned.

The next morning, after a sleep-in, the four of us decided to push on to Lake Tahune.

So far the weather had been fine, but there were no guarantees it would stay that way.

The Frenchmans Cap area is one where the Parks and Wildlife Service notes that “rain normally falls on 15 to 20 days each month during summer and more often in other seasons”.

It would be fair to say that the beauty of the ancient moss-covered myrtle beeches, sassafras and other rainforest species that cover the sheltered slopes beneath Barron Pass were apparent to me on the walk out of Frenchmans Cap, but not on that second morning as we grunted up the inclines.

During that two-hour ascent my mind alternated between a succession of banal pop songs, that had somehow become lodged in my mind and were now being played on high rotation in my head, and focusing on the track markers. After spotting a marker I’d promise myself a rest when I reached that point, then I’d will myself on to the next and insist that all along I had meant the next marker was the rest spot.

Using this combination of self-deluding head games and my internal FM station from hell, I managed to make the top of Barron Pass just in front of the other three, if only to get my mind back on the scenery. The pass is an exposed saddle bookended by quartzite: the slender pinnacle of Nicole’s Needle and the squat bulk of Sharland’s Peak. When I called down and told the others that I’d made the top the news was met with a mixture of joy and responses that promised murder if it wasn’t so.

We spent the time at Barron Pass lunching on flatbread, cheese and salami and simply staring at the vast bulk of the snow-white rock of Frenchmans Cap.

After lunch we left Barron Pass and headed dramatically downwards before the track climbed once more before gaining a ridgeline. From there we descended into the sheltered and surreally green Artichoke Valley, with its soft beds of sphagnum moss and the plentiful pineapple grass from which it derives its name.

From there it was up some steep metal stairs to the top of another ridge around some hillsides, and a sharp descent until suddenly Tahune Hut appeared out of the trees. It had been almost 5 hours since we’d left Lake Vera.

Lake Tahune itself is a place of immense beauty that is best described by E. T. Emmett in his indispensable 1953 and sadly out-of-print book Tasmania by Road and Track: “The immediate surroundings of this sepia pool are pines, and right out of it for a sheer couple of thousand feet rise the white cliffs of Frenchmans Cap’’.

Tahune Hut was built in 1971 to replace the original that was destroyed by fire. It is small and cosy with room for 16 at a pinch but better suited to about 12. We shared the hut with six others: five people from Sydney’s central coast and a well travelled Irishman who walks mostly in Scotland.

We awoke on the third day to weather that was more spring than summer – windy, cool and threatening rain. Within hours, however, summer had returned. With the prospect of 360-degree vistas on the top of the mountain we packed our daypacks and headed up the serpentine walker’s track that takes you to the top of the mountain.

The track to the top has changed in recent years and now avoids the north col which is undergoing intensive rehabilitation work. Instead the 450m ascent takes a zig-zagging path up durable rock shelves and a couple of low-angled rock slabs. It’s a steep climb but after two days of heavy packs it felt like a stroll to the shops.

Less than an hour later we were standing on top of the Cap on a near perfect day. Out west we could see the jagged shores of Macquarie Harbour and the shining sands of deserted beaches. To the north we picked out Tasmania’s highest peak Mount Ossa and the other significant high points in the Cradle Mt-Lake St Clair National Park. Closer to Frenchmans we simply marvelled at how the ancient peaks protruded like bones from the verdant skin of the heavily forested earth.

When surveyor James Sprent became the first person to officially climb the Cap in 1853, Tasmania was still known as Van Diemen’s Land and the transportation of convicts had only stopped the previous year. Amazingly 153 years later the vistas that Sprent enjoyed are little changed from the views that we spent two hours absorbing.

Sprent would have been surprised by the westerly view, which now includes the vast man-made hydro-electric impoundment called Lake Burbury. But his surveyor’s soul would probably have rejoiced over the engineering feat that is the Lyell Highway.

For us urban-dwellers the view was extraordinary simply because in every direction that we looked humanity appeared to be absent. Lake Burbury could have been a natural lake and the Lyell Highway – visible here and there – was devoid of cars. Everywhere else was simply mountains and unbroken tracts of forest.

After two hours of visual feasting only the banality of hunger and the promise of stodgy, freeze-dried Mexican chicken, bulked up with Deb instant potato, drew us back down the mountainside. That night, as we ate our carbohydrate-rich concoction, I felt the first pangs of what in the next few days would become regret. Tomorrow when we began the walk back our adventure would be drawing to its end.

The next morning, after accepting that the trip was more than half done, it seemed more pragmatic to focus on the positive side of returning to the inhabited earth. So if climbing the Cap was the single motivator for the three-days before, drinking beer and eating a huge counter meal at the Derwent Bridge Hotel was the dual motivator for our return to civilisation.

Our return journey to the Lyell Highway covered the same ground but it asked less of us: our diminishing food made our packs lighter and there were more down hills than ups. The two-day walk out took us a total of eight hours with plenty of time to stop and enjoy what we’d missed coming in. In comparison it had taken us 12 hours to cover the same distance during the walk in.

On a day that we emerged from the bush the temperature again reached 30 degrees C. After several hours spent washing clothes, swimming and relaxing on the rocky shores of the Franklin River the call of the unwild became stronger than ever.

By late afternoon the six of us were back together, this time sitting in the cool dimness of the Derwent Bridge Hotel. Still wearing the same clothes we’d worn on and off for the past five days, we drank beer like it was the tannin coloured Lake Tahune water, which it resembled. We spoke tiredly and sporadically of a trip now fast becoming a memory.

And whether it was simply tiredness or the softness of the hotel’s couches I’m not sure, but at times I felt myself momentarily absent, the beer glass in my hand tipping dangerously. It was as if I was back there, among the white sun-warmed rocks, on top of a mountain peak shaped liked a tooth, drinking in the views.